The History of Santa Croce

Santa Croce, the largest Franciscan church in the world, encompasses the history of art and faith in Western culture in its entirety and, from its earliest days, it has been a fundamental beacon of attraction associated with St. Francis of Assisi, Italy's patron saint since 1939.

The Building

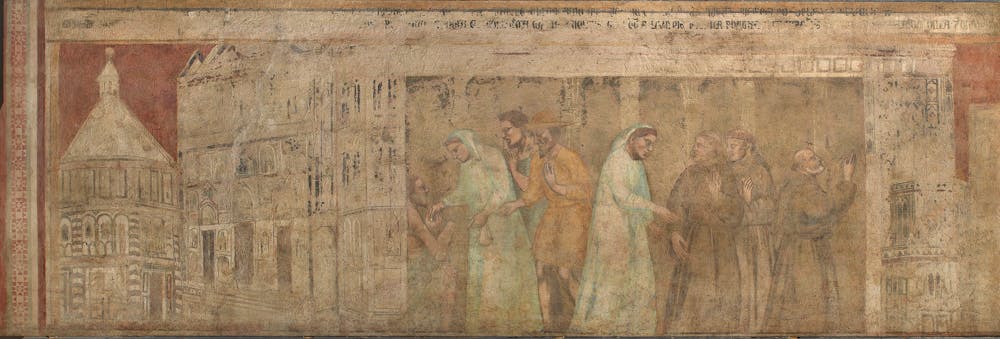

According to tradition, Francis's first companions reached Florence as early as in 1209. The city at the time was thriving on the manufacture of woollen cloth, which it exported throughout Europe, and hundreds of peasants were leaving their fields to find work in the city, moving into new suburban settlements built just outside the walls. The brothers in the new mendicant orders tended to settle among these new city-dwellers, the Franciscans choosing the north bank of the Arno, a low-lying, marshy area often flooded when the river broke its banks. The church of Santa Croce was first mentioned when Francis was canonised in 1228, two years after his death.

Pietro Nelli (attributed), The First Franciscans Come to Florence , late 14th century, Santa Croce, Museo dell'Opera

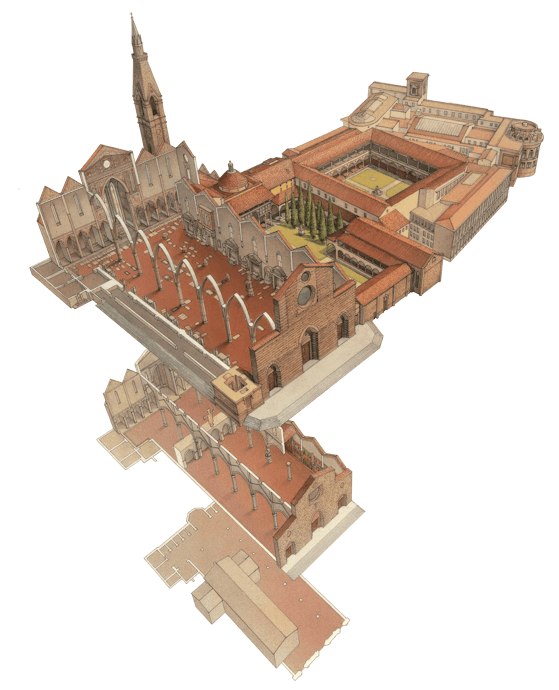

The early church was replaced by a second church built between 1252 and 1267 but it, too, soon proved too small to contain the rapidly expanding congregation and so a much larger complex was designed. The current church's foundation stone was laid on 3 May 1294 (or 1295, there is some dispute over the year). The project was masterminded by Arnolfo di Cambio, Florence's leading architect, and the chancel area was almost complete when he died, some time between 1302 and 1310.

After the transepts, construction began on the nave and aisles and the church was complete by the end of the 14th century, though it was not consecrated until 1443, by Pope Eugene IV. Santa Croce, its shape echoing the habit of St. Francis, has chapels opening onto the transept and two side aisles separated from the nave by piers joined by pointed arches. The typical verticality of Gothic churches is alleviated here by a walkway running above the arches and by the ceiling, where wooden trusses have taken the place of rib-vaulting. In the 14th century artists began to decorate the walls in fresco, a rapid and economical way of narrating biblical stories in a manner immediately clear to a mostly illiterate congregation.

Interior of the Basilica of Santa Croce

A rood screen, used in convent churches to separate the religious from the congregation, was built between the fourth and fifth piers. The screen was on two levels with chapels which, together with the other altars, the paintings, the stained-glass windows and other temporary furnishings, gave the interior church or very jumbled and colourful feel.

Historical levels in Santa Croce

16th Century Renovation

In 1566 Duke Cosimo I de' Medici commissioned Giorgio Vasari to renew the convent churches of Florence, thus including Santa Croce, in order to bring them into line with the dictates of the Council of Trent. Vasari demolished the rood screen, which had prevented the congregation from seeing the high altar, and set a large ciborium or canopy above the altar for the Eucharist, thus turning it into the focal point of the whole sacred arrangement in an effort to reaffirm Christ's true presence in the consecrated host, a point disputed by the Protestant Reformation. Also, to remedy the visual disarray that hampered the symmetry and decorum demanded by the Counter-Reformation, fourteen new, symmetrical altars were erected along the aisle walls and the earlier frescoes and chapels were eliminated.

Florentine painter, Interior of the Basilica of Santa Croce, mid of 19th century. Santa Croce's Historical archive

Santa Croce, "lieu de mémoire"

Over the centuries Santa Croce has become a "lieu de mémoire ", the Pantheon of an entire nation. Initially housing the graves of Franciscan friars, it soon became the burial place of choice for the neighbourhood's wealthier families, who were commemorated by gravestones on the floor in an attempt to conjugate a desire to indicate their place of burial with the wish to appear humble in keeping with the ideals of the mendicant orders.

Tomb slabs on the floor of the Basilica

The tombs of Leonardo Bruni and Carlo Marsuppini, both Chancellors of the Florentine Republic, bear witness to Santa Croce's transition to the role of guardian of the city's glories. The tradition of using the church to honour the great and good was revived by Cosimo de' Medici for Michelangelo in 1564. Napoleon's edict banning burials in churches on grounds of health and hygiene prompted Ugo Foscolo in 1807 to compose his poem I Sepolcri in which he points to Santa Croce as a " lieu de mémoire ", the church housing "Italy's glories" whose virtues must serve as a source of inspiration for all! Santa Croce was thus transformed from the city's Pantheon into the Pantheon of the Italian nation.

Antonio Canova, Monumental Tomb of VIttorio Alfieri , 1804–10. Basilica of Santa Croce, south aisle

In consideration of the church's new-found importance, the need was felt in the 19th century to complete its hitherto unfinished façade which was terminated in 1865, tying in with the celebrations held to mark the 600th anniversary of Dante's birth. Santa Croce was elevated to the honorific rank of Basilica in 1933. Its role as Italy's Pantheon inspired the decision to use a part of its undercroft to honour the memory of those who had "fallen for the Fascist ideal" as part of a drive to impart legitimacy to Fascism in a nationalistic sense. The shrine was officially inaugurated in 1934, and in 1937 the large space beneath the sacristy was chosen to commemorate the Florentine soldiers who had died in the Great War. In the aftermath of World War II the area was transformed and dedicated to those Florentines who had "fallen for the fatherland since the First World War". Damaged in the flood of 1966, Santa Croce has been the object of intense restoration both in its structure and in its works of art.