Tombs and memorials

For centuries the sacred spaces in churches, convents and confraternities received the mortal remains of the deceased, housing their graves to keep their memory alive for posterity, a duty that has always been a feature of Santa Croce.

Tomb slabs

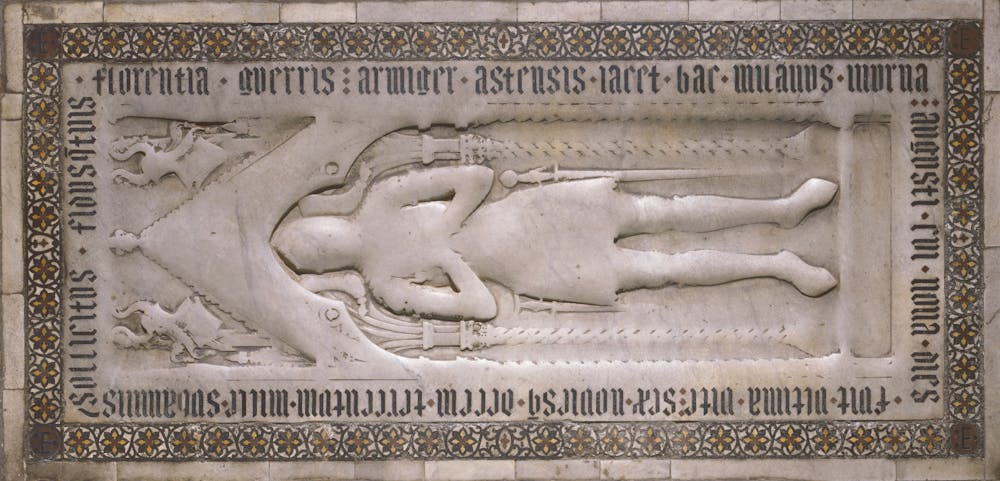

At first these tombs were simple gravestones on the floor – a type mentioned "per contrappasso" by Dante on the terrace of the proud (Purgatorio, XII, 16-19) – reserved for Franciscans who had held important roles in the order, for members of the neighbourhood's most powerful families and for great military captains. Thus Biordo degli Ubertini (†1348) is commemorated by a slab showing the deceased soldier in armour framed by a tabernacle in the Gothic style.

Tomb slab of Biordo degli Ubertini, 1365–70. Basilica of Santa Croce, south transept

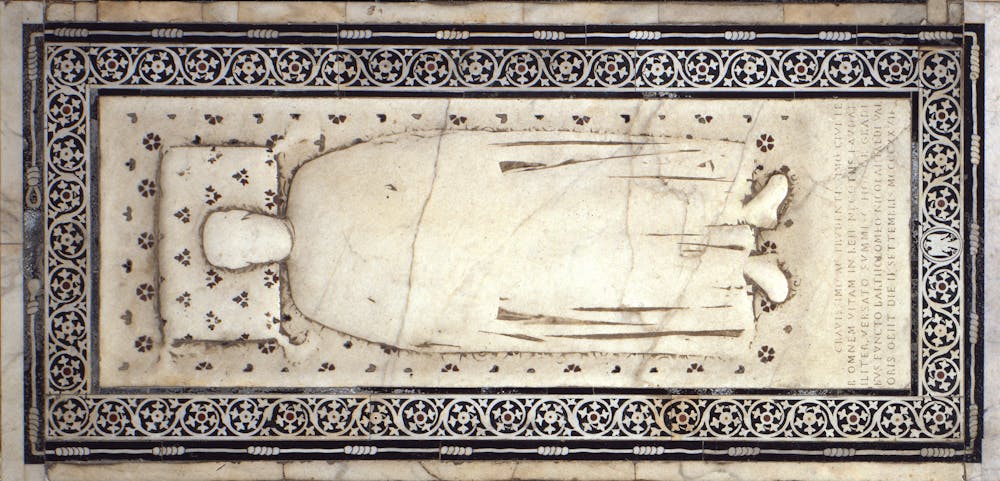

The earliest example of a Renaissance tomb, the Tomb slab of Bartolomeo Valori (†1427) by Lorenzo Ghiberti, was to serve as a model for many others: portraits became more realistic with the elimination of the tabernacle, and allowance was made for the fact that they would be viewed from above. This form of burial lasted for centuries, as we can see from the Art Nouveau Tomb slab of Emilia Toscanelli Peruzzi (†1910).

Lorenzo Ghiberti, Tomb slab of Bartolomeo Valori, 1427. Basilica of Santa Croce, north transept

The 14th century and new monumental tombs

A new style of funerary monument that came into fashion in the 14th century consisted of a sarcophagus with additional sculptural elements. Examples in the church include Giovanni di Balduccio's Baroncelli Monument (c. 1328-30) and the Tomb of Gualterotto de’ Bardi attributed to Agnolo di Ventura (c. 1337). The two tombs in the Bardi di Mangona Chapel (1337-41) are the only ones combining sculpture and painting.

The two tombs in the Bardi di Mangona Chapel (1337-41). Basilica of Santa Croce, north transept, Bardi di Mangona Chapel

The Renaissance

The renewal of the wall-tomb type in the Renaissance style was inaugurated by Bernardo Rossellino's Monument to Leonardo Bruni (c. 1446–50), the prototype of the style and a direct source of inspiration for Desiderio da Settignano's Monument to Carlo Marsuppini (1454–9).

Guardian of Florence's glories

The erection of these momuments to two former Chancellors of the Republic by order of the city fathers bears witness to Santa Croce's transition to the role of guardian of Florence's glories, a tradition perpetuated by the Monuments to Michelangelo, Galileo and Machiavelli. Foscolo, in his Sepolcri written in 1807, points to the church as a place to be dedicated to the memory of the great and good whose virtues must serve as a source of inspiration for all. He himself was to be granted a monument in Santa Croce, although not until 1938.

Pantheon of the Italians

Santa Croce was thus transformed from the city's Pantheon into the Pantheon of the Italian nation, and it was Canova's Monument to Vittorio Alfieri, completed in 1810, that marked the start of a tendency to view the complex in accordance with Foscolo's vision. This was followed by the Cenotaph of Dante Alighieri (whose mortal remains are in Ravenna), erected between 1819 and 1829 in order to celebrate the poet in consideration of the lofty civic value that Santa Croce had acquired.

In the early 19th century Florence started to become very popular with foreigners, particularly of French, Polish, Russian and English extraction, and several of them wished to be buried in the church or in the Cloister of the Dead. Given that they do not celebrate "Italy's glories", however, their memorials tend to afford priority to the depiction of the intimate and private aspect of grief. Stefano Ricci's Monument to Michal Bogoria Skotnicki (1815), a Polish citizen, was the first monument ever to be dedicated to a foreigner in the church, and the Countess Zofia z Czartoryskich Zamoyska, portrayed on her sick bed by Lorenzo Bartolini in 1837-44, was also Polish. The French who remained in Florence after the Restoration included Napoleon's sister-in-law Julie Clary Bonaparte, who was buried in Santa Croce in a tomb carved by Luigi Pampaloni in 1845. Louise de Favreau and the eccentric sculptress Félicie de Fauveau who carved her tomb (now in the loggia against the south wall of the church) in 1855-56 were also French, while inside the church stands the Monument to Louise of Stolberg-Gedern, the Countess of Albany and last flame of Vittorio Alfieri, for whom she commissioned Canova's mastepiece.

Félicie and Hippolyte de Fauveau, Monumental tomb of Louise de Favreau, detail, 1855-1856. First cloister, upper loggia

Musicians

The Monument to Luigi Cherubini (a cenotaph carved by Odoardo Fantacchiotti in 1869) reminds us that Music, too, has a presence among the tombs in Santa Croce, as we can also see from Luigi Pampaloni's Monument to Virginia De Blasis, a singer who died at a very young age in 1838 and the Monument to Gioachino Rossini created by Giuseppe Cassioli in 1900–2)

Odoardo Fantacchiotti, Monument to Luigi Cherubini, 1869. Basilica of Santa Croce, north transept

The 19th and 20th centuries

Countless figures earned the right to a memorial or a monument in the complex in the 19th and 20th centuries, but only a handful were women. Florence Nightingale was one of them.

The practice of raising memorials to illustrious Italians continued in the postwar years with Enrico Fermi commemorated by a bronze medallion cast by Corrado Cagli in 1968 and placed in the north aisle to celebrate the great physicist in 1995.

Corrado Cagli, Memorial to Enrico Fermi, 1968. Basilica of Santa Croce, north aisle

Fascism and the memory of two World Wars

To impart legitimacy to Fascism with an incisive presence in the national Pantheon, the undercroft was redesigned in the 1930s to house the "Shrine to the Fallen for the Fascist Revolution" (removed in the '50s) and the "Shrine of the Soldiers" who died for the homeland in World War I.

Insights

Discover the tombs of the great men buried in the monumental complex: